Despite the best efforts of Clint Eastwood, Kevin Costner and a handful of other Hollywood directors and stars, the Western is largely a forgotten genre in these morally tangled times, its narrative simplicity and black-and-white verities elbowed aside by 150 shades of gray. Yet the taming of the frontier, even as portrayed in the Western, was never as morally straightforward as it seemed. We’re still wrestling with its legacy in the controversies over the Washington Redskins and Johnny Depp’s portrait of Tonto.

Directed by John Ford, “The Searchers” is widely recognized not only as the greatest American Western but as one of the best Hollywood films of all-time. It is beloved by Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and Martin Scorsese, all of whom saw it when they were aspiring young filmmakers and were deeply influenced by it. Largely overlooked in its time — it got no Academy Award nominations — it has captivated three generations of filmgoers.

Just as Ernest Hemingway noted that “all modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called ‘Huckleberry Finn,’ ” film critic Stuart Byron once declared, “in the same broad sense it can be said that all recent American cinema derives from John Ford’s ‘The Searchers.’ ” The film’s images — the door of a frontier cabin swinging open to reveal the vast grandeur of Monument Valley in the film’s opening moment, and closing again at the end; Indians stalking a small band of Texas Rangers on a vast horizon; two lone riders set against a blazing evening sunset — are among the most majestic in all of American cinema and the most copied. The emotions of sadness, grief, lost love, terror and defiance that it captures are among the most resonant. Set against its poetry, power and passion, films like “Django Unchained” and “The Lone Ranger” feel like Happy Meals or kids’ toys.

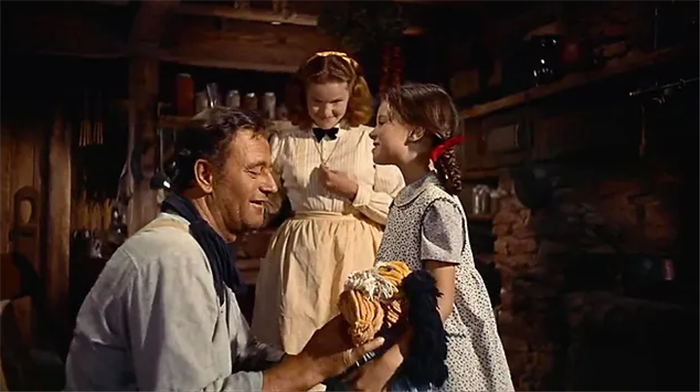

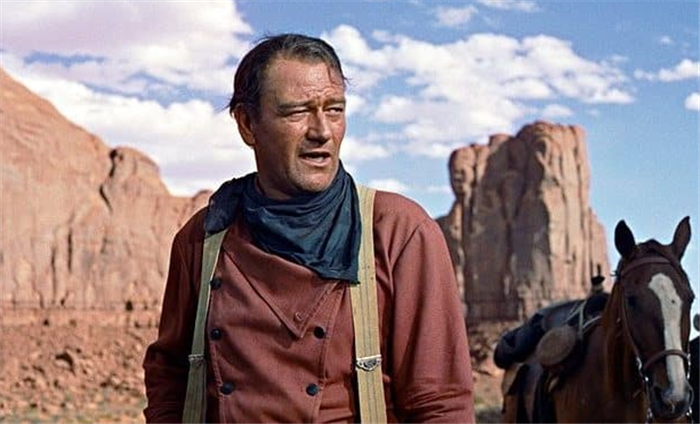

Ford is responsible for the film’s visual poetry — its skill in moving from the intimacy of domestic interiors and family life to the terrible beauty of the gothic sandstone cathedrals and vast obliterating plains of Monument Valley, where its outdoor scenes were shot — as well as its deep and unsettling emotions. But at the heart of “The Searchers” is Wayne’s towering performance as the angry, vengeful Ethan Edwards. From the beginning of his quest, it is clear he is less interested in rescuing Debbie than in wreaking vengeance on the Comanches for the slaughter of his brother’s family. And as time goes by, and she grows from a child into a young woman, he resolves to kill her because she has come of an age to become a Comanche wife and has been physically and spiritually polluted by her contact with Indians.

“Wayne is plainly Ahab,” wrote cultural critic Greil Marcus. “He is the good American hero driving himself past all known limits and into madness, his commitment to honor and decency burned down to a core of vengeance.”

Ethan represents the macho, war-without-end, take-no-prisoners solution to ethnic conflict and terrorism. His modern heir is Maya, the do-whatever-it-takes heroine of “Zero Dark Thirty” — like Ethan a loner who alienates potential allies and co-workers in a single-minded pursuit of justice and retribution against the enemy. Martin Pauley’s goal, by contrast, is to rescue his adopted sister and reunite the remnants of their shattered family. It’s a classic struggle between love and hate, as relevant to today’s extended savage wars as it was when it was released 57 years ago.

Based on Alan LeMay’s taut and powerful novel (which is loosely based on a true story from frontier Texas), “The Searchers” presents a troubling and at times racist portrait. In the opening scenes, Ford depicts Comanches as rapacious barbarians. Yet later in the film, we see a smoldering Indian village in which the corpses of men and women are sprawled in the snow, having been slaughtered by soldiers. And still later we learn that the evil war chief Scar, who led the raid on the Edwards family, had lost two of his own sons to whites. Scar and Ethan become two sides of the same coin, wounded warriors united by hatred.

What will happen when Ethan Edwards catches up with his niece? Will he wreak his terrible revenge? Film critic David Thomson said that “because of its mystery,” he has been compelled to watch “The Searchers” again and again. “And every time, I find, I’m not sure how it’s going to end . . .”

Glenn Frankel teaches journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. This article is adapted from his new book, “The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend” (Bloomsbury 2013).

Leave a Reply