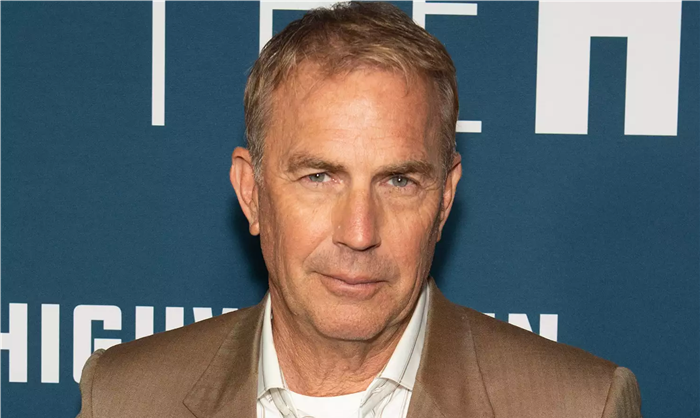

One of three Westerns to win an Academy Award for Best Picture (behind Cimarron and Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven), Dances with Wolves is one of those movies that you just have to experience. Shot between South Dakota and Wyoming, Costner’s directorial debut branded him a Western icon. Not only that, but it’s often been credited with reigniting interest in the Western in the ’90s after a long dry spell following the release of Heaven’s Gate in 1980. But despite the film’s praise, many wonder how historically accurate the three-hour epic even is.

What Is ‘Dances with Wolves’ About?

Three hours is a long time, and it’s even longer if it’s been a while since you’ve seen Dances with Wolves. The film revolves around Lt. John J. Dunbar (Costner at his finest), a Union soldier who, after a fit of bravery during the American Civil War, chooses his next assignment, this time on the Western frontier. Upon arriving at Fort Hays, Dunbar is granted the remote outpost of Fort Sedgwick, though (unbeknownst to him) there’s no record of his assignment. Nevertheless, Dunbar stays and defends the outpost from a local tribe of Pawnee, while simultaneously befriending the neighboring Sioux tribe, namely Stands With A Fist (Mary McDonnell), a white woman who was assimilated into the tribe.

Eventually, Dunbar (who is renamed “Dances With Wolves” by the Sioux after they note his relationship with the lone wolf “Two Socks”) abandons his post and marries Stands With A Fist after the two of them develop a romantic relationship. Unfortunately, Dunbar is soon captured by the U.S. Army, though he’s sprung loose by his new tribe, who welcome him into the fold. Escaping into the mountains, Dances with Wolves ends with our titular hero and Stands With A Fist separating from the Sioux tribe and forging their own path elsewhere.

Who Was ‘Dances with Wolves’ John Dunbar in Real Life?

Believe it or not, there was a real John Dunbar who lived during the events of Dances with Wolves. According to a 1991 issue of The Day, a Connecticut-based newspaper, a man named John Brown Dunbar lived during and served in the American Civil War. What’s more is that Dunbar, born to Christian missionary parents, actually grew up among Native American tribes, specifically the Pawnee (the fictional Dunbar’s sworn enemies in the film). In fact, Dunbar’s father (a Presbyterian minister also named John Dunbar) eventually abandoned his mission after the Pawnee people proved too difficult to convert.

After his time at war, the younger Dunbar used his upbringing among the Pawnee to teach tribal languages at Washburn College in Topeka, Kansas. His notes on the tribe’s culture and folklore were instrumental to George Bird Grinnell’s “Pawnee Hero Stories and Folk-tales,” one of the most detailed accounts of Pawnee history. When asked about the real-life Dunbar, screenwriter Michael Blake revealed that he used the surname after finding it on a roster of Civil War soldiers, not recognizing that there was an actual John Dunbar (not to mention two) who’d lived during that time frame.

“[Costner’s John Dunbar] is definitely a work of fiction,” Blake told The Day, “but generally speaking, the events that took place in Dances With Wolves are all plausible events.” Additionally, Blake used a book by William Nye titled Plains Indians Raiders as the basis for his understanding of Native American culture, and coincidentally, the elder John Dunbar’s own research was instrumental in Nye’s. Of course, the irony is that many, such as University of Nebraska instructor Judith Boughter, consider the Pawnee to be the victims of the Sioux and not the other way around as the movie would have you believe.

Mary McDonnell’s ‘Dances with Wolves’ Character Is Based on Real-Life

But Dunbar isn’t the only historical figure woven into Dances with Wolves, either purposely or not. Mary McDonnell’s Stands With A Fist is likewise based on an actual historical figure, though unlike Dunbar, they don’t actually share a name. The idea that a white woman would be adopted by a Native tribe after they’d first slaughtered her own people may seem preposterous to some, but there’s actually some historical precedent for it. In fact, that exact scenario played out once before, back in the 1800s with a woman named Cynthia Ann Parker.

Kevin Costner’s ‘Dances with Wolves’ Infuses Itself with Historical and Cultural Realities

Beyond the truth that Dances With Wolves is fictitious in nature, many elements from Kevin Costner’s masterpiece are based on reality. For example, although the movie was filmed in South Dakota and Wyoming, there were actual Union bases on the Kansas-Colorado border during that time. No doubt, the Fort Hays and Fort Sedgwick we see in Dances with Wolves are still fictional renditions, but they’re based on the real-life history of that region. While neither is in operation any longer, the former now stands as a historic park while the latter was destroyed in the 1870s.

Furthermore, although the conflict between the Pawnee and Sioux may be a bit misrepresented, the costuming is not. According to Cathy Smith, who spent the majority of her career restoring Native American artifacts, Dances with Wolves set a standard that’s hard to replicate. “I don’t think there has ever been a film about Indians that was done correctly in terms of costumes or props,” she told Entertainment Weekly. “Dressing all these warriors and having them in front of you on horseback going on a buffalo hunt was like going back in time.” And this isn’t to mention Doris Leader Charge (who played Pretty Shield in the film), the Lakota woman who translated Michael Blake’s script into the Lakota language. Much of the film is spoken in Lakota and Pawnee on top of American English, making Dances With Wolves more accurate than most.

“There’s a lot of good feeling about the film in the Native community, especially among the tribes,” American Indian Film Festival director Michael Smith (Sioux) explained in Angela Aleiss’ Making the White Man’s Indian. “I think it’s going to be very hard to top this one.” Of course, not everyone feels that way, and some within the Native American community didn’t appreciate Kevin Costner’s vision. “Lakota has a male-gendered language and a female-gendered language,” Oglala Lakota activist Russell Means noted in 2009. “Some of the Indians and Kevin Costner were speaking in the feminine way. When I went to see it with a bunch of Lakota guys, we were laughing.”

Leave a Reply