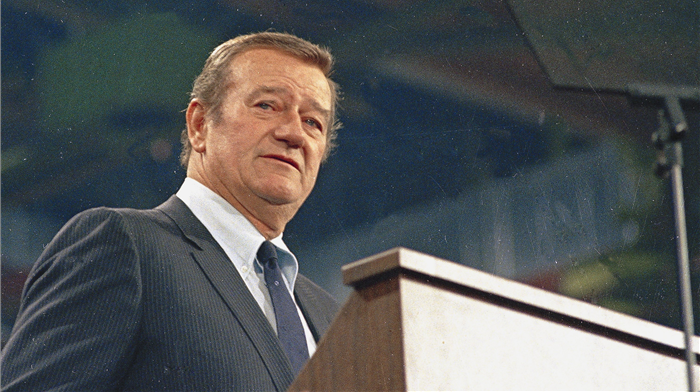

A leading light of a Hollywood past, John Wayne‘s career spanned from the silent era of the 1920s to the Golden Age of Hollywood, through to the American New Wave. Born Marion Martin, in Winterset, Iowa, the actor who became known as John Wayne would define an era of American cinema and, for three decades, would be one of its biggest stars.

However, as with most revisionism, the light of retrospect tends to uncover new faces or angles with which we regard icons of the past. There have been numerous occasions where films, musicians, actors, directors etc., have been shown to be highly problematic, made clear by the passage of time.

Such is the case with John Wayne. At face value, he was the larger than life cowboy, 6ft 3in and the embodiment of modern American ideals — a poster boy for grandmas everywhere. He starred in Stagecoach in 1939, The Searchers in 1959 and famously played cantankerous, one-eyed U.S. Marshall Rooster Cogburn in the original True Grit in 1969. He even directed and starred in The Green Berets (1968) to support the US war effort in Vietnam.

‘Wow, what a wholesome and proactive member of the American movie scene’, you may be thinking. Well, let’s dig a little deeper. Firstly, Stagecoach and most films in the Western genre were, at entry-level, what the late film critic Roger Ebert called “unenlightened”. However, if you were to scratch a little further beneath the surface, it would seem that it was intentionally one-sided.

Directed by John Ford, who collaborated with Wayne on The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Stagecoach seems to embody that side of American culture that the world knows too well, exceptionalism. The Apaches in the film are regarded as savages and that is the extent of it. There is no mention of the fact that the European White man invaded native Americans land and enacted a grinding trail of destruction that started with the arrival of the Mayflower in 1620.

At this point, Wayne could be forgiven for starring in such short-sighted flicks. If someone were to contend that it ‘was the way back then’, or people ‘didn’t think about stuff like that back then’ etc. one may be tempted to renege. As, after all, on-screen John Wayne embodied the true American ideals, and what’s wrong with that? One could also perhaps purport that the Western genre was simply a bit of fun — I know for a fact my grandma would count herself amongst those numbers.

There can be no doubt of his captivating talent as an actor. However, it was John Wayne’s actions off-screen that cause the problems. Regardless of where you sit on the political spectrum, Wayne was an American conservative in the truest sense and used his stature in cinema to advance their causes. The Green Berets came about as a result of this. The film was his successful attempt at rallying support for the ruinous Vietnam War.

That’s fair enough, we’re all entitled to our own political opinions, and it is our democratic right to campaign for causes we deem to be just. Given the time and the prominence the Cold War had on everyday American life, John Wayne came to embody the “democratic” American fight against the evils of communism and The Soviet Union.

Wayne detested communism so much that he played a significant role in creating the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPA) in 1944 and was voted in as its president in 1949. Although the alliance was officially disbanded in 1975, opponents’ accusations of racism and fascism were thrown at it. Ronald Reagan, Walt Disney and Clark Gable were amongst its members. Even Ayn Rand wrote a pamphlet for the organisation in 1947 that criticised what she saw as subliminal communist propaganda in some Hollywood films.

Wayne was so anti-communist that he was an ardent and vocal supporter of the infamous House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). In 1952 he made the political thriller Big Jim McLain, where he starred as a HUAC investigator hunting down communists in the organised labour of post-war Hawaii. This demonstrated his support for the anti-communist hunt.

These personal views also meant that he became a known enforcer of HUAC’s notorious “Black List”, which denied employment and destroyed the careers of many actors and writers who had expressed personal political beliefs that were not in line with HUAC’s. This saw directors such as Sam Wanamaker and Dalton Trumbo blacklisted for “un-American activities.” Other members of the MPA who testified against their peers were Walt Disney, Ronald Reagan and Ginger Rogers.

Typically, Wayne was also an ardent supporter of the chief architect of the “Red Scare”, Senator Joseph McCarthy. Wayne became so world-renowned for his proactive anti-communism that allegedly, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin said that he should have been assassinated for his views, even if the Russian leader was a huge fan of his movies. The Stagecoach star even joined the far-right and paleoconservative John Birch Society in 1960. However, he left after the organisation denounced fluoridation of water supplies as a communist plot.

To some, this may just seem like Wayne was rather committed to his personal politics, to the extent of advocating war and ruining some of his peers’ careers. However, the next moment of his life is the most shocking and reveals him to be highly problematic. In 2019, his 1971 Playboy interview resurfaced, and they make his enrollment in the John Birch Society seem unsurprising. In this historic interview, he made headlines for his contrite opinions on everything from social issues to race relations. This will also make you reconsider the point that his Westerns, such as Stagecoach, were just a bit of fun.

On race relations, he said: “With a lot of blacks, there’s quite a bit of resentment along with their dissent, and possibly rightfully so. But we can’t all of a sudden get down on our knees and turn everything over to the leadership of the blacks. I believe in white supremacy until the blacks are educated to a point of responsibility.”

On the history of America, and its relationship to its native peoples: “I don’t feel we did wrong in taking this great country away from the Indians. Our so-called stealing of this country from them was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed new land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.”

In that infamous interview, Wayne didn’t stop there. He also called Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight’s characters in Midnight Cowboy (1969) “fags” for their “love of those two men”. His seething and bigoted outburst also mentioned American social programmes: “I don’t think a fella should be able to sit on his backside and receive welfare. I’d like to know why well-educated idiots keep apologising for lazy and complaining people who think the world owes them a living. I’d like to know why they make excuses for cowards who spit in the faces of the police and then run behind the judicial sob sisters. I can’t understand these people who carry placards to save the life of some criminal, yet have no thought for the innocent victim.”

It turns out that Wayne had always been a bigot, which is not surprising. Allegedly, at a party in 1957, he confronted Kirk Douglas about his role as Dutch artist Vincent Van Gogh in the film Lust for Life. He was purported to have said, “Christ, Kirk, how can you play a part like that? There’s so goddamn few of us left. We got to play strong, tough characters. Not these weak queers.”

In 1973, Wayne would be criticised publicly by the iconic Marlon Brando. Appearing on The Dick Cavett Show, Brando argued that “We (Americans) like to see ourselves as perhaps John Wayne sees us. That we are a country that stands for freedom, for rightness, for justice.” The Godfather star then added, “it just simply doesn’t apply.”

The above has displayed John Wayne as a problematic bigot. Yes, he was a man of values, but that is seriously undermined by the gravity of his statements and actions. Moreover, that is just the tip of the iceberg, his career was littered with bigoted outbursts, which truly mark him out as one of Hollywood’s most confounding icons.

You may choose to separate the art from the artist, but in Wayne’s case, and for obvious reasons, it is rather tricky.

Leave a Reply