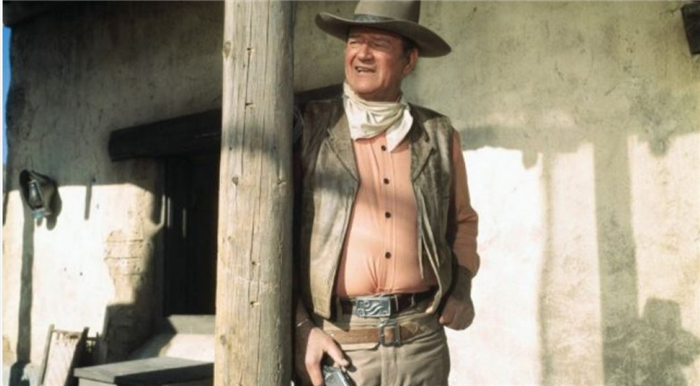

John Wayne managed to monopolize the western genre due to his consistent inventiveness. While Wayne starred in countless westerns, he was able to keep the genre interesting by keeping audiences on their toes. When Wayne disapproved of the way that western characters were interpreted in High Noon, he created Rio Bravo in response; when he sensed that the genre was dying, he appeared in John Ford’s subversive classic The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

Wayne wasn’t above using new filmmaking gimmicks in order to spice up the genre and make it feel fresh again, and given the countless westerns that he appeared in, it makes sense that Wayne would want the genre to keep being inventive. While it isn’t necessarily remembered as one of his best films, Wayne’s 1953 film Hondo was actually shot in 3D. Had Wayne gotten his way, it would’ve been released in 3D too!

‘Hondo’ Was Supposed To Be the First Western Shot in 3D

Hondo was one of the first films released through Wayne’s production company Wayne-Fellows Productions, which was later renamed Batjac Productions. Wayne’s intention was to shoot the film in 3D, an emerging format that had been growing increasingly popular thanks to the success of science fiction films like Creature From The Black Lagoon and It Came From Outer Space. However, the popular 3D films at the time were primarily in the science fiction and western genres — a 3D western had never been attempted. Wayne had the chance to capitalize on the trend and be the first western star to adjust to the emerging format. Although the 3D format made the film feel more exciting for a general audience, it did present some challenges throughout the shoot.

Wayne’s daughter Gretchen said that Hondo’s production was “a challenge when they were making it, because the cameras weren’t perfected like they are now.” The 3D cameras used for Hondo were the size of a truck, which made shooting in the sweltering desert of Chihuahua a challenge for the entire crew. The weather created numerous obstacles and damaged some of the finely crafted sets that were created to resemble Apache villages. The production was also under a strict timetable, as director John Farrow had been set to start another film a few months later. Warner Brothers head Jack Warner reportedly complained that several valuable shooting days were lost due to the constraints with the technology. It was a considerable amount of work put into a film that doesn’t necessarily rank among Wayne’s best.

These 3D “All Media Cameras” utilized two lenses, and maintaining the functionality of both led to numerous delays in the shoot. Transportation was also an issue, as cinematographer Robert Burks was unfamiliar with the technology and had a hard time adjusting to the new format. Farrow’s approach was also quite different compared to other 3D films. Farrow put less emphasis on 3D “gimmicks” and pop out gags. He used the technology to capture a more immersive sense of landscape; there are only a few instances when gunfire or debris flies directly in the audience’s face. While the de-emphasis on gags was a notable stylistic advancement in 3D that other filmmakers would later use to their advantage, it didn’t do much to convince the executives at Warner Brothers that the film necessitated a 3D release. It’s unfortunate that the technology wasn’t ready when considering how many odd films actually were released in 3D.

Warner Brothers Refused to Release ‘Hondo’ in 3D

Although the 3D trend was very popular when Hondo first went into production, interest in the format was beginning to decline as the film reached its tentative release date. Warner Brothers noted that the successful 3D films at the time, such as House of Wax and Dial M for Murder, were using a broader scope of vision, and did not rely on gimmicks. Releasing a film in 3D was also not an easy process; theaters needed a lighter, reflective screen in order to make the film’s 3D effects stand out. These compiling issues inspired Warner Brothers to simply release the film in 2D and abandon the 3D print. Although the audiences at the time did not get to see Hondo in its intended format, a remastered 3D version of the film was eventually released at the Cannes Film Festival in 2007. Wayne claimed that he had “looked for locations and picked the locations where each scene would be shot” in order to emphasize the 3D effects. Wayne claimed that he had found “white molten rock, blue pools of water, black buttes, big chalk-white buttes” that would look great in 3D, but that “Warner Brothers decided to give up and use the Fox system.”

Wayne was ultimately disappointed by the process, but not just because of the 2D release — he also clashed with Farrow on set. While Farrow’s more artistic approach to 3D may have benefited the film’s quality, it led to some creative differences with Wayne on set. Wayne told Film Comment that Farrow “didn’t really have a great deal to do with” the film’s creative inception, it was Wayne who had obtained the rights to Louis L’Amour’s short story “The Gift of Cochise,” which served as the inspiration for Hondo. Although Farrow was an accomplished director, he wasn’t one of Wayne’s regular collaborators like John Ford, Howard Hawks, or Andrew McLaglen. Despite some of the issues that they had with each other, Wayne and Farrow teamed up once more in 1955 for the World War II drama The Sea Chase.

‘Hondo’ Earned Geraldine Page Serious Acclaim

Hondo received significant attention at the time of its release due to the performance by Geraldine Page as Angie Lowe, the young homesteader that falls in love with Wayne’s character. Page had been a popular star on Broadway, and the notion of a prestigious actress joining a blockbuster adventure film like Hondo lent the film more credibility than it may have received otherwise. Page’s performance earned her a surprise Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress, but lost to Donna Reed’s role in the Best Picture winner From Here To Eternity.

The recognition for Hondo was surprising considering that the Oscars have generally been less receptive to westerns. Although Cimarron won Best Picture in 1931, no other western won the top prize until Dances With Wolves and Unforgiven’s victories in the 1990s. In recent years, neo-westerns like Brokeback Mountain, Hell or High Water, and The Power of the Dog earned Best Picture nominations, but were ultimately snubbed of the top prize.

Leave a Reply