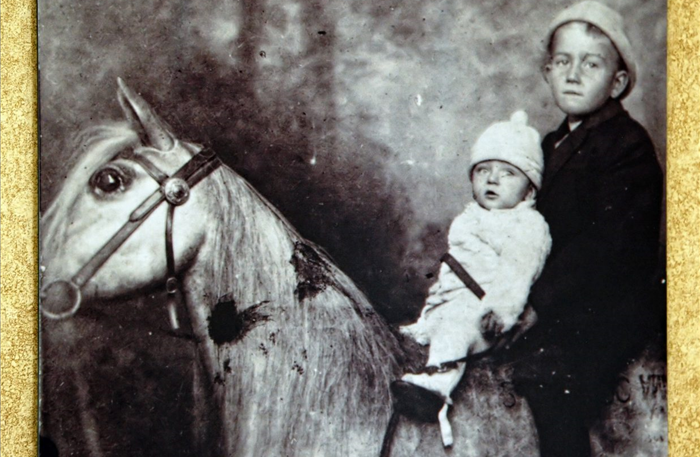

Yep, Mary Brown Morrison was quite a woman. Of course, most Americans—most people across the globe, for that matter—know only her son, born 100 years ago on May 26, 1907, in Winterset. Marion Robert Morrison eventually became Marion Michael Morrison (after his brother Robert’s birth), then Duke Morrison and finally John Wayne. From son of an unsuccessful druggist and “a tiny, vivacious red-headed bundle of energy,” to football player, to honor student at Southern Cal, to bit player and stuntman, to actor, to movie star, Academy Award winner and American icon.

But in my book, anyone who gives birth to a 13-pound baby deserves recognition.

Birth of a Legend

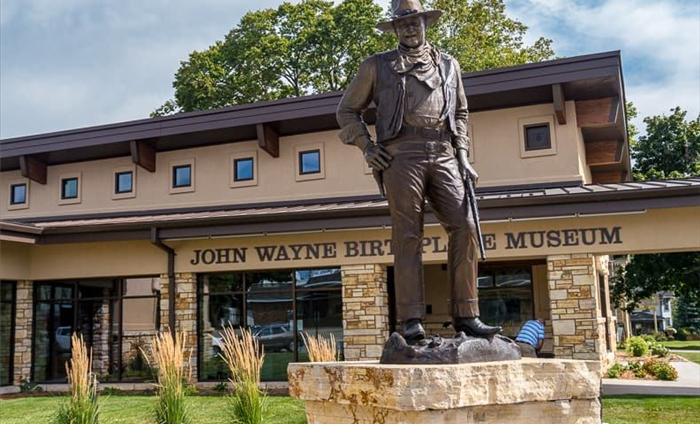

The Morrisons lived in a small, four-room house on Second Street for three years after baby Marion’s birth, then moved 12 miles north to Earlham for three more years and eventually on to California. If you’re following John Wayne, might as well start at the beginning.

Today, the Birthplace of John Wayne includes the house, partially restored to its 1907 appearance, plus a welcome center and gift shop. You’ll find plenty of memorabilia, including his eye patch from True Grit, and photographs and letters. Publicly, Wayne never returned to his hometown (although some say he sneaked home in the 1950s), but Hollywood has. Winterset served as location for Dick Van Dyke’s 1971 comedy Cold Turkey and Clint Eastwood’s 1995 hit The Bridges of Madison County.

In Old Oklahoma

From Iowa, it’s a long drive to Oklahoma City, where the Duke was, and is, a fixture at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

They loved John Wayne at the Western Heritage Awards, giving him Wranglers for The Alamo, The Comancheros, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and True Grit. The museum’s Western Performers Gallery gives him plenty of attention, from his shootin’ irons (his ubiquitous modified 1892 Winchester and single-action revolvers used in The Shootist), wardrobe pieces, even his kachina dolls and other treasures he donated to the museum.

The Duke in Big D

The more I watch True Grit, the more I respect Wayne’s acting. I can even overlook Glen Campbell’s, ahem, acting. The movie was set in Arkansas and Oklahoma, filmed mostly in Colorado, but the Duke came to Big D in June of 1969 to promote his new flick. So I’m heading south to Dallas, Texas.

True Grit opened at four area theaters on June 18. The Duke appeared in person at the Gemini, reportedly propped up on the concession stand with Glen Campbell, stopping traffic on Central Expressway. The Gemini’s pushing up daisies (so is the legendary Astro), but Dallas still has a few grand old theaters, even if you’re more likely to hear live music at the Granada or Lakewood. The Texas Theater, best known as the location of Lee Harvey Oswald’s apprehension after the JFK assassination, has been restored. And folks have been trying to reopen the circa-1945 Casa Linda, which closed in 1999. True Grit also played at the Casa Linda, among the first theaters to open in a shopping center. I saw Misery there. Still have the imprints of my wife’s fingers on my forearm, left during that sledgehammer scene.

Remember the Alamo

Farther south, you’ll find the real Alamo, of course, in San Antonio, but Wayne fans probably enjoy Alamo Village in Brackettville more.

By the late 1950s, rancher-mayor-businessman Happy Shahan had already courted Hollywood (Arrowhead; The

Last Command) to drought-stricken Brackettville, which had seen its population drop from 4,800 to 1,800 after the 1944 closure of Fort Clark. Shahan got Wayne to sign on, building real buildings (not false fronts) for sets for the mission and village. Filming started on September 9, 1959.

Shahan kept Alamo Village, and more movie companies came. Alamo Village remains a destination for tourists and, sometimes, film crews.

“John Wayne enjoyed being in Brackettville,” Shahan’s widow, Virginia, tells me. “He felt it was one place he

could be himself, where the people didn’t bother him.”

Santa Fe and Colorado

Another film location for Wayne was the J.W. Eaves Movie Ranch near Santa Fe, New Mexico. Although the first movie filmed here was The Cheyenne Social Club, John Wayne showed up here for Chisum. Yet he seems to have done some of his best work (Monument Valley aside) up at Buckskin Joe near Cañon City, Colorado, which uses several authentic buildings from around the state. Parts of The Cowboys were filmed here, as was True Grit. Other Colorado locations for True Grit included the Ouray courthouse and scenes at Castle Rock, Montrose, Owl Creek Pass (for the final shoot-out) and Ridgway.

Hmmmm. Buckskin Joe has been really good to actors playing drunken Westerners. Before Wayne took home his Oscar, Lee Marvin won one for his role in Cat Ballou, also shot at the town.

Traveling west, stop at the lively Western town of Durango and hang your hat at the Strater Hotel. After all, Louis L’Amour often stayed in this historic hotel—he said it inspired him—and while he didn’t write Hondo here, it’s a fun stop. Besides, I think Wayne’s performance in Hondo was one of his best and most understated.

Down Arizona Way

Moving on into Arizona, one more movie town is left on my agenda. Walking the streets of Old Tucson, recognizing the hillside and the saguaro backdrop, I can’t help but give a little John Wayne walk and, a la Rio Bravo, call out, “Burdette. Nathan Burdette.”

No one even gives me odd looks.

Although the studio was first built in 1939 for Arizona and served TV’s High Chaparral admirably, Wayne fans will also remember the set for McLintock!, El Dorado and Rio Lobo. Well, maybe they’d best forget Rio Lobo.

If your feet are sore, now is a good time to head south to Nogales and let the legendary Paul Bond fix you up with a pair of custom cowboy boots. After all, the 91-year-old Cowboy Hall of Fame inductee also stuck leather on John Wayne’s small feet.

But true Wayne fans know to head north to the White Mountains and the 26 Bar Ranch near Eagar. In the 1960s, Wayne and partner Louis Johnson bought the 64,000-acre ranch, raising purebred Herefords until Wayne’s death. Today, the 26 Bar is owned by the Hopi Tribe of Arizona, and the main house serves as a B&B. A museum is also in the works.

If ranching is not your strong suit, you can always mosey over to Flagstaff and the historic, circa 1927 Hotel Monte Vista. The John Wayne Room is No. 402.

Hollywood or Bust

It’s on to Los Angeles, where the Duke is still a star.

There’s his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame … his 1950 handprints and footprints at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre (sand for the cement came, reportedly, from Iwo Jima) … a statue of the Duke on horseback on Wilshire Boulevard. If you’re lucky enough to get a VIP tour at Warner Brothers Studios, the museum may be more Harry Potter today, but there’s still some Duke memorabilia. Alas, the only celebrity I spy while eating lunch is the back of John Amos’ head (Amos is best known for his role as James Evans, Sr. on Good Times).

The Autry National Center’s Museum of the American West is not to be missed, either. Besides, Wayne isn’t the only Western icon turning 100 in 2007. Gene Autry also entered this world in 1907, and the museum he founded is among the best collections of Western artifacts (historical and Hollywood) in the country.

High and Mighty in the OC

The drive from LA to Orange County can be as dangerous as that wagon ride in Angel and the Badman, but it must be done. By the mid-1960s, Wayne had left the Hollywood scene for his Arizona ranch and, more frequently, his home in Newport Beach. He lived here until his death, often sailing his yacht on the Pacific. His home has been torn down, but The Wild Goose is available for rental, if your pockets run deep.

I’ll pass on setting sail (hey, I remember how Wake of the Red Witch ends!) to find his statue at John Wayne Airport instead. Yep, Orange County named its airport after the Duke.

The end of the trail for the Duke came on June 11, 1979, when he died of stomach cancer at age 72. Wayne was buried in Newport’s Pacific View Memorial Park. For years, the grave remained unmarked, but the family finally put up a headstone.

“Tomorrow is the most important thing in life,” his marker reads. “Comes into us at midnight very clean. It’s perfect when it arrives and puts itself in our hands. It hopes we have learned something from yesterday.”

I expected to find “Feo, Fuerte y Formal,” the Spanish saying he said he wanted for his epitaph.

“He was Ugly, Strong and had Dignity.”

Leave a Reply